Delores Hamilton

Photos

Title

Delores Hamilton

Identifier

NC27518-001

Interviewee

Delores Hamilton

Interviewer

Karen Musgrave

Interview Date

7/21/06

Interview sponsor

Moda Fabrics

Location

Cary, North Carolina

Transcriber

Karen Musgrave

Transcription

Karen Musgrave (KM): This is Karen Musgrave, and I am conducting an interview with Delores Hamilton for Quilters' S.O.S. - Save Our Stories. I am conducting this interview by e-mail, beginning on July 16, 2006. Thanks, Delores, for agreeing to this interview. Tell me about the quilt you selected for this interview.

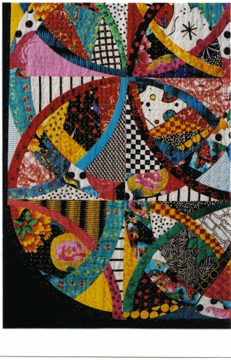

Delores Hamilton (DH): I started "Circular Progressions" in Sylvia Einstein's class at Empty Spools in Asilomar, California. Sylvia has used some traditional patterns but then, varying them, she has created contemporary quilts. When I go to a class, I typically want to do something a bit different from everyone else, and Sylvia immediately encouraged me to 'go for it.' Although I used some of her ideas for a contemporary double-wedding ring (such as the fat and skinny arcs), I created two original blocks based on her idea and started cutting fabrics and putting them on my design wall. When I had all of the fabrics up on the wall, arranged just exactly how I wanted them, someone accidentally knocked against the board and the board fell face forward. There was a collective gasp in the classroom, but I just shook my head in recognition. I make so many mistakes in my work that I now call them 'creative opportunities,' and Murphy's Law definitely applies to my work, not to mention my life. I restored the fabrics--couldn't remember the way I originally had them--and then muttered under my breath for days as I constructed them. I swore off piecing for about a year after making this quilt. When it came time to bind it, I knew I wanted a thin, unobtrusive binding. As I was auditioning fabrics, it occurred to me that if I turned the quilt upside down, I could cut off a corner along a curve of one of the arcs for a dash of interest. Most of my quilts are totally original pieces, so you may think it odd that I chose this one. Unlike some art quilters who stretch the definition of 'quilt' into almost a new meaning, I like my work to evoke quilting's traditional roots, even when I make art quilts. People who recognize my quilts without looking at the signage tell me that it is my use of color that identifies my work. "Circular Progressions" is typical of my use of color: bright, pure colors and lots of black and white fabrics. It's also typical of my quilting. Although I can quilt in the traditional way and have even hand-quilted a king-sized bed quilt I made for a raffle quilt for the North Carolina Quilt Symposium one year, I prefer quilting in a style I've seen on some quilts made by African Americans: the big stitch. I use perle cotton and to make stitches about 1/4-inch long, give or take, to hand-quilt much of my work. I like the texture, I like the Zen state I go into as I do the handwork, and I feel a bit of a woo-woo connection to generations of quilters who came before me.

KM: Who taught you to quilt? And when did you begin?

DH: Although I'd made a bed quilt for my daughter in 1973 and a baby quilt later, that was long before I took my first quilting class. I did not know what I was doing. I didn't even quilt the baby quilt because it didn't occur to me that the batting would slip and bunch up. In 1988, when my marriage was deteriorating quickly, I enrolled in Regina Liske's 8-week quilting class offered through Wake Community College, more for respite than to learn quilting. Regina believed that a college course should have content as well as technique, so for each 3-hour class, she spent 1-1/2 hours taking us through the history of quilting. In the last 1-1/2 hours, she taught us basic techniques, all done by hand. At the end of the first 3-hour class, I was jazzed up from the realization that I could combine my sewing skills with my art skills (I'd been drawing and painting for decades). I announced to Regina that I wanted to make 'art quilts,' a term I thought I'd coined on the spot. Regina just smiled. I had no idea at the time that there was a growing movement of art quilters or that Regina was a member of it herself. By the end of the course, I had almost finished the top of a small sampler quilt. On January 9, 1989, just when I had prepared the quilt for hand-quilting, the Raleigh area got hit by an ice storm. I was introduced for the first time to the term 'black ice' when I took one step on my seemingly wet driveway, only to have my feet fly out from under me. In my hard landing, I broke my right arm. I am right-handed. Undaunted, I quilted that quilt by hand with my arm in a cast. I was definitely hooked!

KM: You've talked a little about taking a class and your influences, so I'd like for you to expand upon these topics. What other classes have you taken? And who would you say has influenced your work?

DH: I am basically a class junkie; I love to learn. Considering I have averaged about five classes per year in the 18 years I've been quilting, just a selected list of classes and teachers would stretch over the next gazillion words or so. I'll list quite a few but be grateful I'm not listing all of them--as if I could remember all of them. In the beginning years, I wanted to learn all of the basic techniques so that if I later chose to deviate from them or chuck them completely, perhaps my work would still show some residual evidence of technical competence. I thought I'd reach that goal in five years. So much for my ability to estimate (and perhaps a little hubris): It took twice as long. For these years, I credit the following teachers for giving me the skills to continue: Jane Hall, (hand appliqué and foundation piecing; Ann Fahl, contemporary foundation piecing; Elly Sienkiewicz, hand appliqué (and who also encouraged me to move beyond the traditional); Judith Baker Montano, embroidery for crazy-quilts; Sharee Dawn Roberts, machine-embroidery; Michael James, design; Erika Carter, contemporary design; and Joen Wolfram, strip-piecing. Once I realized I could combine vacations and classes, new opportunities opened up. I became a devotee of the craft colleges, particularly Penland in the mountains of western North Carolina, Arrowmont in the Blue-Ridge Mountains in eastern Tennessee, and Haystack Mountain in Deer Isle, off the coast of Maine. At Penland in separate classes, Susan Wilchens Brandeis and Jane Dunnewold taught me every aspect of surface design, including how to dye and paint all of the clothes and shoes I wore, an accidental learning experience. After 2-1/2 weeks with Carol Shinn, whose work requires vocabulary beyond 'magnificent' and 'incomparable,' I began to get the knack for sewing pictorial work on canvas. I still get heart-palpitations when I see her work. Arrowmont introduced me to Christine Zoller and her techniques for dyeing and painting silk as well as many shibori techniques. And at Haystack, I dove into the deep end and took two weeks of innovative design classes with Nancy Crow. (On the first weekend--thanks to a brilliant suggestion from Mac McNamara--we all made green cards and came up with names representative of the Crow Company's sweat-shop environment. I now answer to "Guadeloupe.") I also signed up for quilting cruises and quilting tours. As a 50th birthday present to myself, I signed up for Doreen Speckmann's first Caribbean cruise. At sea, I learned curved piecing from Judy Dales, color theory from Judy Warren Blaydon, and absolute zaniness from Doreen, herself. Two years later, I joined her for her tour of Australia, where I took an appliqué class on native flowers from an Australian quilter at the Austral-Asian Quilt Symposium, where Doreen was a featured speaker. My motto became: 'Learn to quilt. See the world.' Subsequently, I went to India, Japan, and Tuscany, the latter for a phenomenal class from an equally phenomenal quilter, Esterita ("Teri") Austin. (Note to Teri: Does that plug get me some free Misty Fuse?) The place that I'm most grateful for is Quilt/Surface Design Symposium (QSDS) in Columbus, Ohio. The first time I went, I took a class with Virginia Avery. By the end of the week, I wanted to adopt her as well as to pattern my life after her amazing life. But the most incredible experiences happened because, for the first time, I was completely surrounded by people who did the kind of work I did. No one rolled their eyes when I showed them photos of my art quilts! I was enchanted, amazed, and felt like I'd discovered Nirvana. I've came back many times after that: Sue Benner, my most memorable teacher, who even sent me some of her own personal photos to use afterwards, based on what I'd created in her class; Pauline Burbidge, who showed me the value of creating a design from torn paper first, and Liz Axford, who taught about structured design and a limited color palette, helping me realize that my personality isn't suited for working that way, a valuable lesson for me to learn. I also attended Katie Masopust Pasquini's Alegre Retreat in Santa Fe, New Mexico, taking a class from her on fractured landscapes. David Walker also taught a fusing class there, and he applauded when I finally gave up on the elaborate piecing technique Katie taught and moved to the Dark Side (fusibles) for my final project. In all of these venues, I learned the value of spending at least a week (preferably two weeks) away from home, immersed in my art--no cooking, no cleaning, no errands, no high-pressure job, no rush-hour traffic, no TV. Ah, bliss! These classes made me yearn for--no, crave-- retirement so I could do my own workday after day after day. In addition, I want to pay homage to the artists who took the time to write some of my favorite books. I learned from them, too. Here's the short (cough, cough) list: Beyond the Horizon, Valerie Herder; Pieced Flowers, Ruth McDowell; Quilts! Quilts!! Quilts!!!, Diana McClun and Laura Nownes; Blockbender Quilts, Margaret Miller; One-of-a-Kind Quilts, Judy Hopkins; Free-Style Quilts, Susan Carlson; The Nature of Design, Joan Colvin; The Art of Annemieke Mein, Annemieke Mein; The Art of Joan Schulze, Joan Schulze; Design Basics, David Lauer and Stephen Pentak; The Quilter's Book of Design, Ann Johnston; The Quilted Garden, Jane Sassaman; The Fabric Makes the Quilt, Roberta Horton; The Art Quilt, Robert Shaw; Surface Design for Fabric, Richard Proctor and Jennifer Lew; Sky Dyes, Mickey Lawler; Surfaces for Stitch, Gwen Hadley; Colors Changing Hue, Yvonne Porcella; A Spectrum of Quilts, Caryl Bryer Fallert; A Painter's Approach to Quilt Design, Velda Newman and Christine Barnes.; Spirits of the Cloth, Carolyn Mazloomi. If you're wondering if I'm ever going to mention who influenced me the most, now I reveal a major clue: Check the last book in the list above all. It is not a single person, as it turns out, who influenced me; it is a 'collective who': African American quilters. My introduction to their work came at a showing of quills at the Ackland Art Museum, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. These quilts were made by mothers and their daughters from Oakland, California. As I walked into the first room of the exhibit, I was stunned, enthralled, and captivated as I took in a style of work I'd never seen before. The exuberant colors, put together in unusual but exciting ways, were my colors. The designs reflected a freedom that I'd never dared to try. I felt liberated just from looking at them. And their stories--ah, their poignant stories--gave me insights unlike any I'd ever heard from other quilters. One story remains with me. A daughter wrote about making her first quilt (it was in the show) using a green and white plaid. Most of the blocks were constructed loosely in the same general way, but one was bigger and completely wonky. She said that she took that block to her mother and told her that she'd made a mistake. Her mother looked at the block and then at her. Then she said something beyond my experience, something close to this, 'You didn't make a mistake; you just put yourself into your quilt.' Oh, to have a mother who was that affirming and supportive instead of the do-it-over-until-you-get-it-right kind of mother. I envied that daughter! Ironically, the wonky block hardly stood out at all, and I didn't notice it until I read the write-up on the quilt. Why? Well, the quilter may have run out of the green and white plaid, or she may have decided her quilt needed a spark, but for whatever reason, she had added one red-and-white block near the bottom of the quilt. It made that quilt stunning! At the end of the exhibit, I decided that I wanted to experience that kind of freedom as I worked, that kind of pizzazz, and that kind of fearlessness in design and color combinations. I haven't even come close. However, I'm not on my deathbed yet; I still have time.

KM: Please share some more with me about your creative process. Do you work every day? Do you plan things out or let them unfold, etc.? What are you working on now?

DH: Most of the time, I have an idea in mind, sometimes perfectly visualized, other times vaguely imagined. I neither keep a journal of ideas nor work in a series, although this loud voice in the back of my head (I call the voice 'Gretchen') tells me frequently that I can't possibly be a real artist if I don't do either of these. Usually, however, I'm only interested in trying something new and different, so there are built-in challenges--that means 'problems'--with each piece I make. Occasionally I see potential construction problems in the design step, but does that stop me? Noooooooo. I take a Scarlett O'Hara approach, telling myself I'll think about that tomorrow. Frequently, I get ideas in the middle of the night, so I'm convinced my subconscious continues trying to solve these problems as I sleep. At this point, with the design in my mind, I get quite excited. New! Different! Never done before! (By me) My adrenaline kicks in and I go into overdrive. I can barely wait for the design to materialize. Because much of my work is pictorial, I usually draw the elements on printer paper to try out my ideas. When I have enough drawings to work with, I frequently make a full-size cartoon of the major elements on sheets of butcher paper, cut them out, and play with the pieces, forming a beginning composition on my design wall. A few times, I've made a quick painting of my initial design, usually to get the values clear in my mind. I'm definitely a believer in the saying, 'Value does all of the work; color gets all of the credit.' With the design reasonably set, I usually have a clear idea of the colors and possible fabrics to use. The fabric-auditioning process begins then, also a guaranteed adrenaline-rush. I have a huge supply--okay, a small quilt shop--of commercial and hand-dyed cotton fabrics. In addition, I've collected a respectable variety of specialty fabrics, including everything from sheers to upholstery fabrics. I pull out every fabric that might possibly work, quickly covering my huge, bare cutting table with stacks and stacks of fabrics. I have no qualms about mixing commercial fabrics with hand-dyed fabrics in a piece. I look for color, texture, and values and I will cut right into the center of a fabric if that's the area I want in a particular place. Little by little, I narrow down my choices of fabrics that might work. Although some people gasp at this, I often cut pieces from multiple fabrics to audition them. The rejected pieces go into my 'collection' of scraps, which are organized in bags by color--did I mention that I'm somewhat compulsive? With the colors and fabrics decided, I begin cutting out and assembling the pieces, sometimes fusing the various elements to muslin backgrounds so that I can move them around easily; other times, piecing the fabrics or hand appliquéing them. Often, I combine multiple construction techniques. The best way to construct the piece usually develops over time just as the right way to quilt the piece does once, I'm done with the construction. Less often, I use some of the lessons from Nancy Crow's innovation classes, working without any plan in mind, pulling fabrics at random and then letting them direct the composition. I like this way of working, and yet I'm still insecure about what I produce. Frequently, these pieces turn out to be abstract compositions, something I'm trying to create more and more of now. That's my current focus, a focus that ravages my confidence in my design skills. How do I communicate a cohesive idea in an abstract way? What makes one abstract composition effective and another a dismal failure? Why am I doing this when pictorial quilts are so much easier for me? When faced with these types of questions, I typically buy more books. Okay, that's an excuse, but it works for me. I love books. In this case, most of the books I've bought do not focus on textile art, but on abstract paintings. Strangely, I'm comfortable painting abstracts, but not using fabrics to create abstracts. Gretchen tells me that this makes no logical sense, but I assure her that it's still true. So, today as I answer these questions, I'm back in learning mode. In a couple of days, I'll start pulling fabrics to see if I can develop something that works, and the whole process is still mysterious for me. As for working, I try to do something related to my artwork every day, although I also make altered books and jewelry, so it's not always creating quilts. This is a luxury of time that I still appreciate beyond measure after being retired for five years. I'm not a morning person, so I muddle through the early hours (you know, 10:00 a.m. - noon). After lunch, I'm fully awake--thanks to caffeine infusions--usually working on all eight cylinders, and ready to start working, 'usually' being the key word in that scenario. On good days, I dive in, totally focused on my work, but within two hours, the apparent maximum limit to my attention span, I lose interest and have to take a break. Afterwards, I can return for another two-hour stint. On bad days--I have fibromyalgia and chronic-fatigue syndrome--I try to work on something simple, such as stringing beads for a bracelet. For me, it's a balancing act: trying not to work so hard that I push myself into a chronic-fatigue episode, but still continuing to do some meaningful work each day. When possible, I also try to do some handwork if I watch TV in the evenings, the only time I have the TV on.

KM: I'd like to talk about the aesthetics, craftsmanship and design aspects of quilts in general. What do you think makes a quilt artistically powerful?

DH: It's tempting to respond with 'I don't know,' and 'Next question, please.' I do know that my aesthetics don't always match the aesthetics of the judges who critique quilts or the jurors who select quilts for an exhibit. Undoubtedly, I'm not alone when at a show or an exhibit I occasionally mutter under my breath, 'What were they thinking? 'They' being the artists or the jurors. Other times, I rhapsodize over the brilliance of the selections except when my work isn't selected, too. An Award of Excellence is bestowed on one quilt, and I am astonished that it wasn't awarded to another far-superior quilt that clearly deserved it. In other cases, I find myself not only agreeing that this or that work deserves to be in the exhibit and/or to receive an award, but also defending a specific piece to someone else who is sneering at it. Of course, not everyone has my perfect taste (cough, cough). It's all so confusing at times, and I find myself beseeching the universe to tell me just who is it who decides what is great art? Where's the unqualified answer? Believe me; it's not in my answer to these questions. For me, design and composition rule in evaluating all artwork. Throw in color and texture next, and then pull it all together with technical competence. Sounds like a formula, doesn't it? So, how come we can't all make it work? I do know what I look for when I evaluate art: virtuosity, the unexpected surprises, the unique vision, messages, points of view, stunning visual effects, seductiveness, drama, and delightful details inviting close inspection. I usually know I've found a winner when my mouth drops open, and I stand transfixed by the work. All of those characteristics mean something specific to me. I can point out artists that exemplify these traits in their work, only to find that you may not agree. That's okay. I don't really expect your aesthetics to be identical to mine, despite my 'perfect taste' comment above.

KM: What advice would you give a beginning art quiltmaker?

DH: As most of my friends know, I am full of advice--well, that's what I call it and I am willing to offer it even when it's not requested; that's just the kind of helpful person I am. Give me a person who wants to begin making art quilts, and I will inundate him or her with an avalanche of advice, scraps, encouragement, some fusible, cheerleading, some batting, and support. At that point, he or she may wander away muttering about trying sculpture, but for the beginner who is strong of heart, I'm there for him or her. In fact, if you'll give me two beginners, I can drop this awkward 'him or her' and 'he and she' business and get to the point. In short, I know what helped me begin, and I would share my experience in hopes that some of it would also be helpful to the new art quilters who have come to sit at my knees. I had technical skills up the wazoo and a natural feel for color, but despite years of drawing and painting, I still lacked confidence in my design and composition skills. I would naturally assume that my beginners were in the same boat, up the same creek, and missing their respective paddles. Next, I would get up onto my soapbox--I carry it with me everywhere--and exhort them to sign up for design classes, good, old basic design classes, ones that might not even use fabrics for the exercises, that might just use black and white construction paper, instead. I would point them to teachers who actually have backgrounds in design, such as the elite among us, AKA artists with BFAs, MFAs, or equivalent degrees who are willing to teach basic design classes. I would prepare them to feel humbled in these classes as seemingly everyone around them produces fabulous results for each exercise while they are convinced that their results might work to line a bird cage if the bird wasn't too picky. I would also share my original goal with the hapless beginners, which was to be able to create work just like 'real' artists would--you know artists who actually seem to know what they are doing. What a concept! I would even posit the theory that design, and composition comprise the platform upon which good art is built. Doesn't that sound pedantic enough to be believed? Okay, color, line, form, and probably a high-protein breakfast needs to be in there, too, but it's all theory, anyway until my beginners start making their first pieces. When they have a few design classes under their belts or bras or wherever they keep them, I'd send them off to more classes, this time ones with art quilters who have designed classes especially for beginners. Preferably, these will be ones who combine design skills with experimentation and beginner-appropriate critiques. Some beginners actually take good photos, and those could serve as the base for a landscape quilt. My beginners wouldn't want to do anything that normal, however, unless they could use colors that deviate wildly from any that are likely to exist in nature. But I thought I'd pass the idea along, just in case. For those semi-reckless newbies who want to jump right in, I would suggest that they start with the known and move to the unknown, such as a traditional pattern they could modify. They could play Harry Potter (Dumbledore simply cannot be dead!) and conjure up curved lines where straight lines existed before. They could unmercifully attack the block with swords or scissors, cutting it up and reassembling it into a desirable new design. Instead of making a series of like blocks set in a predictable grid, they could enlarge their new design, make it the focal point of a small composition, and extract subsets from it to form repeating echoes of the main image or whatever. If they could be trusted not to cut off their fingers, they could cut a two-inch square into a larger piece of cardboard and slip-slide it around over magazine photos or advertisements until they had an 'aha!' moment, seeing a pleasing set of lines and shapes that could metamorphose into something fun to work on. Or, by adding a glue stick to their arsenal, they could cut and paste elements of those ads or photos to form an intriguing, plausible design for a quilt. The computer-literate could even whip out their laptops, call up their favorite design programs, and use the electronic tools to transform a number of traditional designs. For the truly reckless, that is, artists who work in other media and thought they'd give quilting a try, I'd just encourage them to jump right into the deep end. They probably wouldn't ask me for advice, anyway, but they might want me to pretend to be the lifeguard in case they need some technical advice along the way. I would cheerfully toss out the life-ring, haul them to the edge, speak my words of wisdom, and then send them back in again. In sum, I'd try to stay out of their respective creative ways. Dripping pool water over their fabrics may be the next 'in technique, after all.

KM: You are truly wonderful. Tell me about your studio.

DH: Depending on your viewpoint, my 'studio'--note the quotes because I never think of it as a real studio--is either two small bedrooms in my house or my entire house and 1/4th of the two-car garage. There are definite advantages to living alone! Generally, though, I confine my quilting to the two bedrooms and store the overflow of supplies in the garage. I refer to the smallest room as 'the sewing room.' I doubt that I could get another thing in that room and still be able to move around. It contains: a sewing table, desk, an old paint-it-yourself dresser, a tall cabinet for paints and dyes, shelving to the ceiling on three walls, a tall 7-drawer plastic unit for all of my sheers, a storage unit that contains about 1/2 of my thread collection (the rest is on the shelves or a unit on a nearby wall), a tall, wide ironing board which is always up, a small ironing board next to the sewing machine, a small TV/VCR, a large light-box, and an odd-shaped closet with my Asian fabrics, non-cottons, yarn, and other oddities, such as bolts of fusible. In addition, I've added a lot of artwork to my sewing room, including one large quilt (mine), one small quilt by Jette Clover, and prints of four of cat quilts done with upholstery fabrics by Jude Sparks. It gives me great pleasure to work in there as a result. The other room, 'the project room' has a project table that takes up most of the center of the room. I had it built to my height (5' 10", only I'm shrinking in my dotage!), and it sits on two bases of drawers, including four drawers filled with two banks of file folders. I save way too much stuff! There are open spaces at the top of the drawers for rulers, drawing pads, cutting mats, and so on. The surface of the table is impervious to pins, so with a cutting mat, I use it to cut fabrics, and without the cutting mat, to pin-baste quilts. One wall is taken up by wall-to-wall bookcases 12-ft. wide and 7-ft. tall. The upper half, the shelves, is filled mostly with quilting and craft books. And yes, they are organized by type. Books on quilts from France? Upper left, second shelf. Books on surface design? Lower right, bottom shelf. The lower half of the bookcases contains four narrow drawers and four cabinets. There is another taller, narrower bookcase in another corner, and it holds all of the books that are two large to fit on typical shelves. The double closet is filled floor-to-ceiling with fake wood shoe-shelves where I store my cotton fabrics, both hand-dyed and commercial. Does it come as a surprise at this point if I tell you that the fabrics are neatly folded and organized by color and type? Although non-quilters gasp when I show them that closet (I don't mention the fabrics in the other room), I just smile because I have a friend in New Mexico who has an entire room devoted to her cotton fabrics, all stored on floor-to-ceiling shelves, including shelves in the middle of the room. And that's just her cottons. But I digress. I also have an 8 ft. x 8 ft. design wall, covered in felt. I often wish it were twice that big because I occasionally make (gasp!) bed quilts. The last one--I'm still working on it--is 135 x 120 inches. For the arithmetically impaired, that does NOT fit on my design wall. There is very little room to display any art in that room, but there is a small quilt (mine) behind the door, a small piece by BJ Adams next to the design wall, and a papier-mâché pig's head clock (the tongue wags like a pendulum when the clock actually works) above the door. And there are a few more pigs on top of the bookshelves and scattered on some of the shelves. If you're starting to detect artifacts of a pig collection, you are a good detective. And that's my 'studio.' Oh, wait. Okay, a little truth in advertising: There are more fabrics and batting stored in plastic containers in the garage, under my king-sized bed, and in the linen closet. Then, there are maybe 25 boxes of projects in my clothing closet, which I refer to as WIPs (works-in-progress) because I continue to delude myself into thinking that someday I'll actually finish them. In my other clothing closet, I've stored my finished quilts. And in the dining area of the great room, there is a chest completely filled with beads, some of which I actually use on my quilts. As I said, some people--I won't mention names--consider my entire house my studio.

KM: I've heard a lot of people say that quilt artists don't collect other people's work, but I have not found that to be true. Tell me more about the artwork you collect.

DH: Before I begin, I need to tell you a story about my penchant for collecting art. When I moved to Atlanta in 1974, my house had a formal dining room, my first one. I wanted a genuine table and chairs but couldn't afford them, having spent my paltry savings on the down payment. My parents sent me $500 to buy the furniture, which wasn't a lot, but better than nothing, so I went shopping at some of the less-expensive stores. At the first store, I saw a life-size stone sculpture of a walrus in the display window. We fell in love; at least I think it was mutual. The signs said, 'Everything on sale, 50% off!' so I went in, saw that the walrus was $350, felt I could afford $175, and tried to buy it. The salesman said, 'That piece is not on sale.' I protested. He stood firm. I protested louder. He stood firm. I protested. Well, you get the point. Apparently, my voice projected to the office in the back of the store by this time because the manager came out (he didn't even have to ask what the problem was) and told the salesman to sell it to me for half-price and to help me load it into the front seat of my '69 Dodge Challenger. We received a number of double-takes on the ride home. That was my first dining room set. The next weekend I brought back a large mirror that looked like it had been made out of 12 hubcaps. I thought it was cool to see myself reflected 12 times every time I looked in the mirror. This was my second dining room set. The next time I came home with a bas-relief fish, my third dining room set. It was at that point that I realized that I'd rather have art (remember: 'art' is a relative term) than a functional piece of furniture. I did buy a cheap dining room set about a year later; I still have it. One more quick story: When I moved up here to Cary, North Carolina, it was on IBM's dime, and the company paid for packing as well as moving. My pictures alone required 200 picture boxes, which gives you another glimpse of my collection gene. The walrus required a custom-built crate, which is now the workbench in my garage. A preamble to my current collection: I am somewhat fond of my own work, so my quilts are in every room of the house, including both bathrooms. I know, I know: Quilts don't belong in the bathroom or the kitchen, but I just figure I can make more if these get ruined. However, I do collect other artists' work, some of which I mentioned in the previous question/answer. Here's a partial list, your opportunity to practice speed-reading.

• "Raku Cliffs/Red," Sharron Parker, two-piece felted wall hanging

• "Skyview," Ruth Carden, quilt (Quiltswap)

• Untitled, Anna Williams, quilt

• "Red Flowers," Kathie Briggs, quilt (Bag-O-Stuff)

• Untitled, small quiltlet, Pat Autenrieth

• "Cat with Flowers," unknown artist, San Blas reverse appliqué

• "Lady with Fishes," unknown artist, San Blas reverse appliqué

• Untitled, unknown artist, hand-embroidered quilt, India

• Untitled, unknown artist, metallic, hand-embroidered wall hanging, India

• "Jellyfish," unknown artist, hand-dyed velvet-resist

• Untitled, paper collage, Karen McCarthy

• "Women with Dove," unknown artist, hand-painted paper prayer mat, Tibet

• Untitled, spirit doll, unknown artist

• "Log Cabin," Carol Owen, 3-D handmade, hand-painted paper construction

• "Spirit House," Carol Owen, multimedia assemblage

• "Somebody's Darling," Keith Lo Bue, computer-manipulated photos

• "Maple Leaf Branch," C. Brinkley, metal sculpture

• "Seaside Fishing Shack," Sue Lyons & Lindsay Peterson, metal sculpture

• "Pitti Palace View," Renzo Scarpelli, mosaic in Pietre Dure

• "Pig Family," Ventura Fabian, Oaxaca wood carving, hand-painted

• "Reindeer," Bili Mendoz Mendez, Oaxaca wood carving, hand-painted

• "Pelican," C. Olsen, wood-carved sculpture on wood "pilings"

• "Red Wing," Bart Forbes, watercolor, Navajo Chief

• "Ot Way," Bart Forbes, watercolor, Navajo woman

• "Wat-Clurn-Yush," Bart Forbes, watercolor, Navajo Chief

• "Temy," Bart Forbes, watercolor, Navajo young woman

• "Ocean View," Robert Carter, watercolor

• "Carousel Pig," Patricia Baker, watercolor

• "Multiples," Robert Weil, ink & watercolor (print)

• "Oceanside," Dan Poole, oil (print)

• "Pig," James Wyeth, oil (print)

• "Raccoon with Corn," Charles Harper, acrylic (print)

• Untitled, Jane Kiser, ceramic vase with inlaid figures

• "Buffalo Butterfly," Darrell Taliman China, Acoma pot

• "Pig," Joyce L., Acoma clay sculpture

• "Egret," Jack App, etching

• "Mary Pigford," G. Mac Narmed, etching

• "Sir Francis Bacon," G. Mac Narmed, etching

There are more prints, photos, sculptures, ceramics, wood carvings, cloth dolls, etc., but I'm tired and frustrated because some artists don't sign their work. Plus, if you're not convinced now that I collect other artists' work, you'll just have to visit and see them for yourself.

KM: Do you belong to any art or quilt groups?

DH: I vacillate on belonging to groups and going it alone. Since retiring five years ago and starting to work on my art full-time, I've had some revelations about myself, and one of those is that I am not a group person. I actually prefer to work alone on my art most of the time. That surprised me because I've been a member of an unbelievable number of groups in my adult life. When I first started quilting, I joined the local guild and remained a loyal member for 10 years. Early on, I became a member of a quilting bee formed by members of the guild. I lasted there for several years. I was the only art quilter in that group, and although I admired traditional work and was supportive of the other members, they didn't really know what to make of most of my work. We would frequently travel to various quilting events, which was a good way for me to be introduced to larger quilt shows than the ones in this local area. Eventually, I wearied of defending what I was creating and dropped out. After that, I began attending a group of a dozen quilters that was split almost evenly between traditional quilters and art quilters. Eventually, I was juried into that group and remained a member for a number of years. There were and still are fantastic quilters in that group. The group did a number of group projects, and although I enjoyed many of those, I realized that I was spending most of my time on group projects and not on developing my own work. So, I dropped out of that group. Are you starting to see a pattern here? I joined PAQA-South, stayed for one year and--you guessed it--dropped out. This group did help me grapple with the issue of whether I wanted to be a professional art quilter. I'm not good at marketing myself and my work--hate paperwork, and no longer want to teach. I realized that the effort it takes to be a professional artist wasn't how I wanted to spend my time. I also tried a two-person critique group with an excellent artist. Besides critiquing our own work, we also attended a variety of art-quilt venues, discussing the work in those shows. This gave me more experience critiquing my work and others' work. I lasted in that small group for a couple of years, and then--you got it--dropped out. Currently, there are two art groups that actually do work for me. Well, at least for today (no guarantees about tomorrow). One is Quilt Art, an online group of around 2,500 people who are either interested in learning how to make art quilts or are actively making art quilts. Some internationally known art quilters are on this list, and I find endless inspiration from this group (and a wee bit of frustration when we go berserk over some topics). I've even participated in several Quilt Art challenges, but only when I found ones that fit with work I either wanted to be doing or was already doing. Several online friendships have developed from being on this list, which I also enjoy. Are you wondering how long I've stayed with this group so far? It's a new record: 5 years! The other type of group I like is get-togethers with two to four other artists for art playdates. Sometimes we meet and work independently; other times we all try some techniques together. Usually this is a one-day event, and we have these perhaps once every one to three months. I participate in jewelry, art-quilt, and paper-art play dates on a semi-regular basis. Other than that, I'm a recluse, a hermit, a lone wolf quietly working on my art here at home. Hmmm. Come to think of it, I'm part of another group right here in my little cave: four cats share my space and try to assist me when I'm working. For example, they know that cat fur enhances any fiber work, so the selflessly sleep on the fabrics I have out. When they don't see any fabric sitting out, they have figured out how to open bi-fold doors, which hide (unsuccessfully, as it turns out) shelves and shelves of fabrics for them to pull out and sleep on. Because they know I like texture, during the few minutes each day they aren't eating or sleeping, they sharpen their claws on the felt along the bottom of my design wall. And. because they realize I need extra weight on the quilts I'm trying to machine quilt, all four spread out to hold down strategic areas. With a head start on accumulating cats, I've decided I might as well become the archetypal old lady--one who lives alone, has 60 cats, and talks to herself even when she's out in public. Hey! Someone has to keep up the image.

KM: You really are too funny. Do you think of yourself more as an artist or a quiltmaker, or do you even make a distinction between the two?

DH: Oh, there's that dreaded 'A' word, again! I admit that even though I've been artistic for as long as I can remember, I still stutter through the word 'ar-ar-ar-ar-ti-ti-ti-sssstttt.' I can say I'm a writer and a teacher without showing a scintilla of humility, but to say that I'm an artist strikes me still as downright uppity. And yet, the oppositional-defiant part of my personality (I try hard to hide it; I fail) wants to assert my guaran-damn-tee you right to call myself an artist even if I'm a bad, lousy, upchuck-producing artist. At least I have a museum for my work: The Museum of Bad Art, http://www.museumofbadart.org/. I plan to submit my portfolio soon. When I do have the cajones—'tits' just doesn't have the right ring, does it? --to admit I'm an artist, I have no problems stating that I'm a quilter. I love fabrics, sewing, quilting, and art, and being a quilter means I get to muck around in all of those in one fell swoop. (What is a 'fell swoop,' anyway?) I do usually add that I make art quilts (and altered-books and jewelry), and if the term 'art quilts' perplexes my listener--you now, the blank-stare response--I add, 'think of art quilts as paintings made with fabrics.' Even 5-year-olds get it. When in the company of art quilters, however, I hide my dirty little secret, which is that I make traditional quilts at times, usually for friends or family but also for me, me, me. And--prepare yourself for the shock--I use patterns (gasp!) from books on traditional quilting. I'm not ashamed of doing so, but it does seem to upset way too many art quilters if I admit that. I hate to start a fracas, although I have no qualms about jumping into one if someone else starts one. I also like to use commercial fabrics in my art quilts, despite my extensive collection of hand-dyed fabrics (I 'dye' fabrics using a credit card), which I also love and can occasionally bring myself to use, but only when I have the perfect quilt in mind. And just to make myself absolutely perfectly clear, making quilts is my passion, my love, my fervent calling in life. I can think of nothing that gives me more pleasure. Yes, even more pleasure than what you're thinking right now!

KM: You have given a great interview. Before we close, is there anything else that you would like to add?

DH: It's almost over? Why I've just gotten started on my novel, that is. Will I be inducted into the Hall of Records at The Alliance of American Quilts for the longest interview? I do have something to add, and this is a message to anyone who is considering being interviewed. Do it. If you have the experiences I had, you may discover some things about yourself and your work that you hadn't realized. You may also synthesize some scattered thoughts and unidentified feelings on several issues along the way. I discovered some truths, lies, surprises, and distortions about myself and my work, ones that I didn't realize until I thought through each question, created a draft, and then revised it a number of times before submitting it as my answer. One surprise was my own distorted view of my typical way of working. Until this interview, I would have said, if asked, that I work innovatively most of the time. And yet, when I reviewed just the quilts I've made in the last five years, I realized that I actually planned most of them. Several moments of disbelief latter, I decided that I'd been saying I worked innovatively because that's how I wanted to work and probably because I thought that's the way 'real' artists (instead of the pretenders) actually work. But, in fact, it is easier for me to work when I plan the design first. I draw well, and once I get the design drawn, I'm off and running. Oddly enough, some of my artist friends have only observed me during those times when I have been creating innovatively, so they may be a bit surprised if they get to that Q&A; before they've drifted off into Slumberland. Second, I was surprised by the quilt I picked to go with this interview. The quilt I'm proudest of, "Wildfire," an innovatively created piece using my own hand-dyed silks, seemed to be more of an anomaly. Although it might have been wonderful to have people think that I create art like that as a matter of course, it doesn't represent most of my work. Oddly enough, the quilt I did pick is a variation on a traditional pattern and consists of pieced blocks, and that's not representative of my work, either. But, I found that I had a lot to say about this quilt, and I could draw arrows from it to my other work to illustrate how it fits in. You did notice the arrows, didn't you? Third, I was surprised and horrified by my first cut at the answers. In almost every case, I resorted to pedantic utterings in an attempt, I suppose, to sound like I had something valuable to dispense to my many readers and that I knew what I was talking about. But I got the preachy-teachy 'stuff' out of the way and then returned to writing something resembling who I am and what I wanted to say. Even being true to myself, I found I had way more to say than I thought I would. Of course, I do like to write, as some of you may have figured out by the second paragraph in my answer to the first question. Finally (whew!), I enjoyed the chance to participate in this grand adventure. Contact me if you want the inside scoop on who to bribe so that you can participate, too.

KM: Delores, you have been so much fun to interview and I want to thank you again for taking the time to share yourself and thoughts with me. My interview with Delores ended on July 21, 2006.

Delores Hamilton (DH): I started "Circular Progressions" in Sylvia Einstein's class at Empty Spools in Asilomar, California. Sylvia has used some traditional patterns but then, varying them, she has created contemporary quilts. When I go to a class, I typically want to do something a bit different from everyone else, and Sylvia immediately encouraged me to 'go for it.' Although I used some of her ideas for a contemporary double-wedding ring (such as the fat and skinny arcs), I created two original blocks based on her idea and started cutting fabrics and putting them on my design wall. When I had all of the fabrics up on the wall, arranged just exactly how I wanted them, someone accidentally knocked against the board and the board fell face forward. There was a collective gasp in the classroom, but I just shook my head in recognition. I make so many mistakes in my work that I now call them 'creative opportunities,' and Murphy's Law definitely applies to my work, not to mention my life. I restored the fabrics--couldn't remember the way I originally had them--and then muttered under my breath for days as I constructed them. I swore off piecing for about a year after making this quilt. When it came time to bind it, I knew I wanted a thin, unobtrusive binding. As I was auditioning fabrics, it occurred to me that if I turned the quilt upside down, I could cut off a corner along a curve of one of the arcs for a dash of interest. Most of my quilts are totally original pieces, so you may think it odd that I chose this one. Unlike some art quilters who stretch the definition of 'quilt' into almost a new meaning, I like my work to evoke quilting's traditional roots, even when I make art quilts. People who recognize my quilts without looking at the signage tell me that it is my use of color that identifies my work. "Circular Progressions" is typical of my use of color: bright, pure colors and lots of black and white fabrics. It's also typical of my quilting. Although I can quilt in the traditional way and have even hand-quilted a king-sized bed quilt I made for a raffle quilt for the North Carolina Quilt Symposium one year, I prefer quilting in a style I've seen on some quilts made by African Americans: the big stitch. I use perle cotton and to make stitches about 1/4-inch long, give or take, to hand-quilt much of my work. I like the texture, I like the Zen state I go into as I do the handwork, and I feel a bit of a woo-woo connection to generations of quilters who came before me.

KM: Who taught you to quilt? And when did you begin?

DH: Although I'd made a bed quilt for my daughter in 1973 and a baby quilt later, that was long before I took my first quilting class. I did not know what I was doing. I didn't even quilt the baby quilt because it didn't occur to me that the batting would slip and bunch up. In 1988, when my marriage was deteriorating quickly, I enrolled in Regina Liske's 8-week quilting class offered through Wake Community College, more for respite than to learn quilting. Regina believed that a college course should have content as well as technique, so for each 3-hour class, she spent 1-1/2 hours taking us through the history of quilting. In the last 1-1/2 hours, she taught us basic techniques, all done by hand. At the end of the first 3-hour class, I was jazzed up from the realization that I could combine my sewing skills with my art skills (I'd been drawing and painting for decades). I announced to Regina that I wanted to make 'art quilts,' a term I thought I'd coined on the spot. Regina just smiled. I had no idea at the time that there was a growing movement of art quilters or that Regina was a member of it herself. By the end of the course, I had almost finished the top of a small sampler quilt. On January 9, 1989, just when I had prepared the quilt for hand-quilting, the Raleigh area got hit by an ice storm. I was introduced for the first time to the term 'black ice' when I took one step on my seemingly wet driveway, only to have my feet fly out from under me. In my hard landing, I broke my right arm. I am right-handed. Undaunted, I quilted that quilt by hand with my arm in a cast. I was definitely hooked!

KM: You've talked a little about taking a class and your influences, so I'd like for you to expand upon these topics. What other classes have you taken? And who would you say has influenced your work?

DH: I am basically a class junkie; I love to learn. Considering I have averaged about five classes per year in the 18 years I've been quilting, just a selected list of classes and teachers would stretch over the next gazillion words or so. I'll list quite a few but be grateful I'm not listing all of them--as if I could remember all of them. In the beginning years, I wanted to learn all of the basic techniques so that if I later chose to deviate from them or chuck them completely, perhaps my work would still show some residual evidence of technical competence. I thought I'd reach that goal in five years. So much for my ability to estimate (and perhaps a little hubris): It took twice as long. For these years, I credit the following teachers for giving me the skills to continue: Jane Hall, (hand appliqué and foundation piecing; Ann Fahl, contemporary foundation piecing; Elly Sienkiewicz, hand appliqué (and who also encouraged me to move beyond the traditional); Judith Baker Montano, embroidery for crazy-quilts; Sharee Dawn Roberts, machine-embroidery; Michael James, design; Erika Carter, contemporary design; and Joen Wolfram, strip-piecing. Once I realized I could combine vacations and classes, new opportunities opened up. I became a devotee of the craft colleges, particularly Penland in the mountains of western North Carolina, Arrowmont in the Blue-Ridge Mountains in eastern Tennessee, and Haystack Mountain in Deer Isle, off the coast of Maine. At Penland in separate classes, Susan Wilchens Brandeis and Jane Dunnewold taught me every aspect of surface design, including how to dye and paint all of the clothes and shoes I wore, an accidental learning experience. After 2-1/2 weeks with Carol Shinn, whose work requires vocabulary beyond 'magnificent' and 'incomparable,' I began to get the knack for sewing pictorial work on canvas. I still get heart-palpitations when I see her work. Arrowmont introduced me to Christine Zoller and her techniques for dyeing and painting silk as well as many shibori techniques. And at Haystack, I dove into the deep end and took two weeks of innovative design classes with Nancy Crow. (On the first weekend--thanks to a brilliant suggestion from Mac McNamara--we all made green cards and came up with names representative of the Crow Company's sweat-shop environment. I now answer to "Guadeloupe.") I also signed up for quilting cruises and quilting tours. As a 50th birthday present to myself, I signed up for Doreen Speckmann's first Caribbean cruise. At sea, I learned curved piecing from Judy Dales, color theory from Judy Warren Blaydon, and absolute zaniness from Doreen, herself. Two years later, I joined her for her tour of Australia, where I took an appliqué class on native flowers from an Australian quilter at the Austral-Asian Quilt Symposium, where Doreen was a featured speaker. My motto became: 'Learn to quilt. See the world.' Subsequently, I went to India, Japan, and Tuscany, the latter for a phenomenal class from an equally phenomenal quilter, Esterita ("Teri") Austin. (Note to Teri: Does that plug get me some free Misty Fuse?) The place that I'm most grateful for is Quilt/Surface Design Symposium (QSDS) in Columbus, Ohio. The first time I went, I took a class with Virginia Avery. By the end of the week, I wanted to adopt her as well as to pattern my life after her amazing life. But the most incredible experiences happened because, for the first time, I was completely surrounded by people who did the kind of work I did. No one rolled their eyes when I showed them photos of my art quilts! I was enchanted, amazed, and felt like I'd discovered Nirvana. I've came back many times after that: Sue Benner, my most memorable teacher, who even sent me some of her own personal photos to use afterwards, based on what I'd created in her class; Pauline Burbidge, who showed me the value of creating a design from torn paper first, and Liz Axford, who taught about structured design and a limited color palette, helping me realize that my personality isn't suited for working that way, a valuable lesson for me to learn. I also attended Katie Masopust Pasquini's Alegre Retreat in Santa Fe, New Mexico, taking a class from her on fractured landscapes. David Walker also taught a fusing class there, and he applauded when I finally gave up on the elaborate piecing technique Katie taught and moved to the Dark Side (fusibles) for my final project. In all of these venues, I learned the value of spending at least a week (preferably two weeks) away from home, immersed in my art--no cooking, no cleaning, no errands, no high-pressure job, no rush-hour traffic, no TV. Ah, bliss! These classes made me yearn for--no, crave-- retirement so I could do my own workday after day after day. In addition, I want to pay homage to the artists who took the time to write some of my favorite books. I learned from them, too. Here's the short (cough, cough) list: Beyond the Horizon, Valerie Herder; Pieced Flowers, Ruth McDowell; Quilts! Quilts!! Quilts!!!, Diana McClun and Laura Nownes; Blockbender Quilts, Margaret Miller; One-of-a-Kind Quilts, Judy Hopkins; Free-Style Quilts, Susan Carlson; The Nature of Design, Joan Colvin; The Art of Annemieke Mein, Annemieke Mein; The Art of Joan Schulze, Joan Schulze; Design Basics, David Lauer and Stephen Pentak; The Quilter's Book of Design, Ann Johnston; The Quilted Garden, Jane Sassaman; The Fabric Makes the Quilt, Roberta Horton; The Art Quilt, Robert Shaw; Surface Design for Fabric, Richard Proctor and Jennifer Lew; Sky Dyes, Mickey Lawler; Surfaces for Stitch, Gwen Hadley; Colors Changing Hue, Yvonne Porcella; A Spectrum of Quilts, Caryl Bryer Fallert; A Painter's Approach to Quilt Design, Velda Newman and Christine Barnes.; Spirits of the Cloth, Carolyn Mazloomi. If you're wondering if I'm ever going to mention who influenced me the most, now I reveal a major clue: Check the last book in the list above all. It is not a single person, as it turns out, who influenced me; it is a 'collective who': African American quilters. My introduction to their work came at a showing of quills at the Ackland Art Museum, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. These quilts were made by mothers and their daughters from Oakland, California. As I walked into the first room of the exhibit, I was stunned, enthralled, and captivated as I took in a style of work I'd never seen before. The exuberant colors, put together in unusual but exciting ways, were my colors. The designs reflected a freedom that I'd never dared to try. I felt liberated just from looking at them. And their stories--ah, their poignant stories--gave me insights unlike any I'd ever heard from other quilters. One story remains with me. A daughter wrote about making her first quilt (it was in the show) using a green and white plaid. Most of the blocks were constructed loosely in the same general way, but one was bigger and completely wonky. She said that she took that block to her mother and told her that she'd made a mistake. Her mother looked at the block and then at her. Then she said something beyond my experience, something close to this, 'You didn't make a mistake; you just put yourself into your quilt.' Oh, to have a mother who was that affirming and supportive instead of the do-it-over-until-you-get-it-right kind of mother. I envied that daughter! Ironically, the wonky block hardly stood out at all, and I didn't notice it until I read the write-up on the quilt. Why? Well, the quilter may have run out of the green and white plaid, or she may have decided her quilt needed a spark, but for whatever reason, she had added one red-and-white block near the bottom of the quilt. It made that quilt stunning! At the end of the exhibit, I decided that I wanted to experience that kind of freedom as I worked, that kind of pizzazz, and that kind of fearlessness in design and color combinations. I haven't even come close. However, I'm not on my deathbed yet; I still have time.

KM: Please share some more with me about your creative process. Do you work every day? Do you plan things out or let them unfold, etc.? What are you working on now?

DH: Most of the time, I have an idea in mind, sometimes perfectly visualized, other times vaguely imagined. I neither keep a journal of ideas nor work in a series, although this loud voice in the back of my head (I call the voice 'Gretchen') tells me frequently that I can't possibly be a real artist if I don't do either of these. Usually, however, I'm only interested in trying something new and different, so there are built-in challenges--that means 'problems'--with each piece I make. Occasionally I see potential construction problems in the design step, but does that stop me? Noooooooo. I take a Scarlett O'Hara approach, telling myself I'll think about that tomorrow. Frequently, I get ideas in the middle of the night, so I'm convinced my subconscious continues trying to solve these problems as I sleep. At this point, with the design in my mind, I get quite excited. New! Different! Never done before! (By me) My adrenaline kicks in and I go into overdrive. I can barely wait for the design to materialize. Because much of my work is pictorial, I usually draw the elements on printer paper to try out my ideas. When I have enough drawings to work with, I frequently make a full-size cartoon of the major elements on sheets of butcher paper, cut them out, and play with the pieces, forming a beginning composition on my design wall. A few times, I've made a quick painting of my initial design, usually to get the values clear in my mind. I'm definitely a believer in the saying, 'Value does all of the work; color gets all of the credit.' With the design reasonably set, I usually have a clear idea of the colors and possible fabrics to use. The fabric-auditioning process begins then, also a guaranteed adrenaline-rush. I have a huge supply--okay, a small quilt shop--of commercial and hand-dyed cotton fabrics. In addition, I've collected a respectable variety of specialty fabrics, including everything from sheers to upholstery fabrics. I pull out every fabric that might possibly work, quickly covering my huge, bare cutting table with stacks and stacks of fabrics. I have no qualms about mixing commercial fabrics with hand-dyed fabrics in a piece. I look for color, texture, and values and I will cut right into the center of a fabric if that's the area I want in a particular place. Little by little, I narrow down my choices of fabrics that might work. Although some people gasp at this, I often cut pieces from multiple fabrics to audition them. The rejected pieces go into my 'collection' of scraps, which are organized in bags by color--did I mention that I'm somewhat compulsive? With the colors and fabrics decided, I begin cutting out and assembling the pieces, sometimes fusing the various elements to muslin backgrounds so that I can move them around easily; other times, piecing the fabrics or hand appliquéing them. Often, I combine multiple construction techniques. The best way to construct the piece usually develops over time just as the right way to quilt the piece does once, I'm done with the construction. Less often, I use some of the lessons from Nancy Crow's innovation classes, working without any plan in mind, pulling fabrics at random and then letting them direct the composition. I like this way of working, and yet I'm still insecure about what I produce. Frequently, these pieces turn out to be abstract compositions, something I'm trying to create more and more of now. That's my current focus, a focus that ravages my confidence in my design skills. How do I communicate a cohesive idea in an abstract way? What makes one abstract composition effective and another a dismal failure? Why am I doing this when pictorial quilts are so much easier for me? When faced with these types of questions, I typically buy more books. Okay, that's an excuse, but it works for me. I love books. In this case, most of the books I've bought do not focus on textile art, but on abstract paintings. Strangely, I'm comfortable painting abstracts, but not using fabrics to create abstracts. Gretchen tells me that this makes no logical sense, but I assure her that it's still true. So, today as I answer these questions, I'm back in learning mode. In a couple of days, I'll start pulling fabrics to see if I can develop something that works, and the whole process is still mysterious for me. As for working, I try to do something related to my artwork every day, although I also make altered books and jewelry, so it's not always creating quilts. This is a luxury of time that I still appreciate beyond measure after being retired for five years. I'm not a morning person, so I muddle through the early hours (you know, 10:00 a.m. - noon). After lunch, I'm fully awake--thanks to caffeine infusions--usually working on all eight cylinders, and ready to start working, 'usually' being the key word in that scenario. On good days, I dive in, totally focused on my work, but within two hours, the apparent maximum limit to my attention span, I lose interest and have to take a break. Afterwards, I can return for another two-hour stint. On bad days--I have fibromyalgia and chronic-fatigue syndrome--I try to work on something simple, such as stringing beads for a bracelet. For me, it's a balancing act: trying not to work so hard that I push myself into a chronic-fatigue episode, but still continuing to do some meaningful work each day. When possible, I also try to do some handwork if I watch TV in the evenings, the only time I have the TV on.

KM: I'd like to talk about the aesthetics, craftsmanship and design aspects of quilts in general. What do you think makes a quilt artistically powerful?

DH: It's tempting to respond with 'I don't know,' and 'Next question, please.' I do know that my aesthetics don't always match the aesthetics of the judges who critique quilts or the jurors who select quilts for an exhibit. Undoubtedly, I'm not alone when at a show or an exhibit I occasionally mutter under my breath, 'What were they thinking? 'They' being the artists or the jurors. Other times, I rhapsodize over the brilliance of the selections except when my work isn't selected, too. An Award of Excellence is bestowed on one quilt, and I am astonished that it wasn't awarded to another far-superior quilt that clearly deserved it. In other cases, I find myself not only agreeing that this or that work deserves to be in the exhibit and/or to receive an award, but also defending a specific piece to someone else who is sneering at it. Of course, not everyone has my perfect taste (cough, cough). It's all so confusing at times, and I find myself beseeching the universe to tell me just who is it who decides what is great art? Where's the unqualified answer? Believe me; it's not in my answer to these questions. For me, design and composition rule in evaluating all artwork. Throw in color and texture next, and then pull it all together with technical competence. Sounds like a formula, doesn't it? So, how come we can't all make it work? I do know what I look for when I evaluate art: virtuosity, the unexpected surprises, the unique vision, messages, points of view, stunning visual effects, seductiveness, drama, and delightful details inviting close inspection. I usually know I've found a winner when my mouth drops open, and I stand transfixed by the work. All of those characteristics mean something specific to me. I can point out artists that exemplify these traits in their work, only to find that you may not agree. That's okay. I don't really expect your aesthetics to be identical to mine, despite my 'perfect taste' comment above.

KM: What advice would you give a beginning art quiltmaker?

DH: As most of my friends know, I am full of advice--well, that's what I call it and I am willing to offer it even when it's not requested; that's just the kind of helpful person I am. Give me a person who wants to begin making art quilts, and I will inundate him or her with an avalanche of advice, scraps, encouragement, some fusible, cheerleading, some batting, and support. At that point, he or she may wander away muttering about trying sculpture, but for the beginner who is strong of heart, I'm there for him or her. In fact, if you'll give me two beginners, I can drop this awkward 'him or her' and 'he and she' business and get to the point. In short, I know what helped me begin, and I would share my experience in hopes that some of it would also be helpful to the new art quilters who have come to sit at my knees. I had technical skills up the wazoo and a natural feel for color, but despite years of drawing and painting, I still lacked confidence in my design and composition skills. I would naturally assume that my beginners were in the same boat, up the same creek, and missing their respective paddles. Next, I would get up onto my soapbox--I carry it with me everywhere--and exhort them to sign up for design classes, good, old basic design classes, ones that might not even use fabrics for the exercises, that might just use black and white construction paper, instead. I would point them to teachers who actually have backgrounds in design, such as the elite among us, AKA artists with BFAs, MFAs, or equivalent degrees who are willing to teach basic design classes. I would prepare them to feel humbled in these classes as seemingly everyone around them produces fabulous results for each exercise while they are convinced that their results might work to line a bird cage if the bird wasn't too picky. I would also share my original goal with the hapless beginners, which was to be able to create work just like 'real' artists would--you know artists who actually seem to know what they are doing. What a concept! I would even posit the theory that design, and composition comprise the platform upon which good art is built. Doesn't that sound pedantic enough to be believed? Okay, color, line, form, and probably a high-protein breakfast needs to be in there, too, but it's all theory, anyway until my beginners start making their first pieces. When they have a few design classes under their belts or bras or wherever they keep them, I'd send them off to more classes, this time ones with art quilters who have designed classes especially for beginners. Preferably, these will be ones who combine design skills with experimentation and beginner-appropriate critiques. Some beginners actually take good photos, and those could serve as the base for a landscape quilt. My beginners wouldn't want to do anything that normal, however, unless they could use colors that deviate wildly from any that are likely to exist in nature. But I thought I'd pass the idea along, just in case. For those semi-reckless newbies who want to jump right in, I would suggest that they start with the known and move to the unknown, such as a traditional pattern they could modify. They could play Harry Potter (Dumbledore simply cannot be dead!) and conjure up curved lines where straight lines existed before. They could unmercifully attack the block with swords or scissors, cutting it up and reassembling it into a desirable new design. Instead of making a series of like blocks set in a predictable grid, they could enlarge their new design, make it the focal point of a small composition, and extract subsets from it to form repeating echoes of the main image or whatever. If they could be trusted not to cut off their fingers, they could cut a two-inch square into a larger piece of cardboard and slip-slide it around over magazine photos or advertisements until they had an 'aha!' moment, seeing a pleasing set of lines and shapes that could metamorphose into something fun to work on. Or, by adding a glue stick to their arsenal, they could cut and paste elements of those ads or photos to form an intriguing, plausible design for a quilt. The computer-literate could even whip out their laptops, call up their favorite design programs, and use the electronic tools to transform a number of traditional designs. For the truly reckless, that is, artists who work in other media and thought they'd give quilting a try, I'd just encourage them to jump right into the deep end. They probably wouldn't ask me for advice, anyway, but they might want me to pretend to be the lifeguard in case they need some technical advice along the way. I would cheerfully toss out the life-ring, haul them to the edge, speak my words of wisdom, and then send them back in again. In sum, I'd try to stay out of their respective creative ways. Dripping pool water over their fabrics may be the next 'in technique, after all.

KM: You are truly wonderful. Tell me about your studio.

DH: Depending on your viewpoint, my 'studio'--note the quotes because I never think of it as a real studio--is either two small bedrooms in my house or my entire house and 1/4th of the two-car garage. There are definite advantages to living alone! Generally, though, I confine my quilting to the two bedrooms and store the overflow of supplies in the garage. I refer to the smallest room as 'the sewing room.' I doubt that I could get another thing in that room and still be able to move around. It contains: a sewing table, desk, an old paint-it-yourself dresser, a tall cabinet for paints and dyes, shelving to the ceiling on three walls, a tall 7-drawer plastic unit for all of my sheers, a storage unit that contains about 1/2 of my thread collection (the rest is on the shelves or a unit on a nearby wall), a tall, wide ironing board which is always up, a small ironing board next to the sewing machine, a small TV/VCR, a large light-box, and an odd-shaped closet with my Asian fabrics, non-cottons, yarn, and other oddities, such as bolts of fusible. In addition, I've added a lot of artwork to my sewing room, including one large quilt (mine), one small quilt by Jette Clover, and prints of four of cat quilts done with upholstery fabrics by Jude Sparks. It gives me great pleasure to work in there as a result. The other room, 'the project room' has a project table that takes up most of the center of the room. I had it built to my height (5' 10", only I'm shrinking in my dotage!), and it sits on two bases of drawers, including four drawers filled with two banks of file folders. I save way too much stuff! There are open spaces at the top of the drawers for rulers, drawing pads, cutting mats, and so on. The surface of the table is impervious to pins, so with a cutting mat, I use it to cut fabrics, and without the cutting mat, to pin-baste quilts. One wall is taken up by wall-to-wall bookcases 12-ft. wide and 7-ft. tall. The upper half, the shelves, is filled mostly with quilting and craft books. And yes, they are organized by type. Books on quilts from France? Upper left, second shelf. Books on surface design? Lower right, bottom shelf. The lower half of the bookcases contains four narrow drawers and four cabinets. There is another taller, narrower bookcase in another corner, and it holds all of the books that are two large to fit on typical shelves. The double closet is filled floor-to-ceiling with fake wood shoe-shelves where I store my cotton fabrics, both hand-dyed and commercial. Does it come as a surprise at this point if I tell you that the fabrics are neatly folded and organized by color and type? Although non-quilters gasp when I show them that closet (I don't mention the fabrics in the other room), I just smile because I have a friend in New Mexico who has an entire room devoted to her cotton fabrics, all stored on floor-to-ceiling shelves, including shelves in the middle of the room. And that's just her cottons. But I digress. I also have an 8 ft. x 8 ft. design wall, covered in felt. I often wish it were twice that big because I occasionally make (gasp!) bed quilts. The last one--I'm still working on it--is 135 x 120 inches. For the arithmetically impaired, that does NOT fit on my design wall. There is very little room to display any art in that room, but there is a small quilt (mine) behind the door, a small piece by BJ Adams next to the design wall, and a papier-mâché pig's head clock (the tongue wags like a pendulum when the clock actually works) above the door. And there are a few more pigs on top of the bookshelves and scattered on some of the shelves. If you're starting to detect artifacts of a pig collection, you are a good detective. And that's my 'studio.' Oh, wait. Okay, a little truth in advertising: There are more fabrics and batting stored in plastic containers in the garage, under my king-sized bed, and in the linen closet. Then, there are maybe 25 boxes of projects in my clothing closet, which I refer to as WIPs (works-in-progress) because I continue to delude myself into thinking that someday I'll actually finish them. In my other clothing closet, I've stored my finished quilts. And in the dining area of the great room, there is a chest completely filled with beads, some of which I actually use on my quilts. As I said, some people--I won't mention names--consider my entire house my studio.

KM: I've heard a lot of people say that quilt artists don't collect other people's work, but I have not found that to be true. Tell me more about the artwork you collect.

DH: Before I begin, I need to tell you a story about my penchant for collecting art. When I moved to Atlanta in 1974, my house had a formal dining room, my first one. I wanted a genuine table and chairs but couldn't afford them, having spent my paltry savings on the down payment. My parents sent me $500 to buy the furniture, which wasn't a lot, but better than nothing, so I went shopping at some of the less-expensive stores. At the first store, I saw a life-size stone sculpture of a walrus in the display window. We fell in love; at least I think it was mutual. The signs said, 'Everything on sale, 50% off!' so I went in, saw that the walrus was $350, felt I could afford $175, and tried to buy it. The salesman said, 'That piece is not on sale.' I protested. He stood firm. I protested louder. He stood firm. I protested. Well, you get the point. Apparently, my voice projected to the office in the back of the store by this time because the manager came out (he didn't even have to ask what the problem was) and told the salesman to sell it to me for half-price and to help me load it into the front seat of my '69 Dodge Challenger. We received a number of double-takes on the ride home. That was my first dining room set. The next weekend I brought back a large mirror that looked like it had been made out of 12 hubcaps. I thought it was cool to see myself reflected 12 times every time I looked in the mirror. This was my second dining room set. The next time I came home with a bas-relief fish, my third dining room set. It was at that point that I realized that I'd rather have art (remember: 'art' is a relative term) than a functional piece of furniture. I did buy a cheap dining room set about a year later; I still have it. One more quick story: When I moved up here to Cary, North Carolina, it was on IBM's dime, and the company paid for packing as well as moving. My pictures alone required 200 picture boxes, which gives you another glimpse of my collection gene. The walrus required a custom-built crate, which is now the workbench in my garage. A preamble to my current collection: I am somewhat fond of my own work, so my quilts are in every room of the house, including both bathrooms. I know, I know: Quilts don't belong in the bathroom or the kitchen, but I just figure I can make more if these get ruined. However, I do collect other artists' work, some of which I mentioned in the previous question/answer. Here's a partial list, your opportunity to practice speed-reading.

• "Raku Cliffs/Red," Sharron Parker, two-piece felted wall hanging

• "Skyview," Ruth Carden, quilt (Quiltswap)

• Untitled, Anna Williams, quilt

• "Red Flowers," Kathie Briggs, quilt (Bag-O-Stuff)

• Untitled, small quiltlet, Pat Autenrieth

• "Cat with Flowers," unknown artist, San Blas reverse appliqué

• "Lady with Fishes," unknown artist, San Blas reverse appliqué

• Untitled, unknown artist, hand-embroidered quilt, India

• Untitled, unknown artist, metallic, hand-embroidered wall hanging, India

• "Jellyfish," unknown artist, hand-dyed velvet-resist

• Untitled, paper collage, Karen McCarthy

• "Women with Dove," unknown artist, hand-painted paper prayer mat, Tibet

• Untitled, spirit doll, unknown artist

• "Log Cabin," Carol Owen, 3-D handmade, hand-painted paper construction

• "Spirit House," Carol Owen, multimedia assemblage

• "Somebody's Darling," Keith Lo Bue, computer-manipulated photos

• "Maple Leaf Branch," C. Brinkley, metal sculpture

• "Seaside Fishing Shack," Sue Lyons & Lindsay Peterson, metal sculpture

• "Pitti Palace View," Renzo Scarpelli, mosaic in Pietre Dure

• "Pig Family," Ventura Fabian, Oaxaca wood carving, hand-painted

• "Reindeer," Bili Mendoz Mendez, Oaxaca wood carving, hand-painted

• "Pelican," C. Olsen, wood-carved sculpture on wood "pilings"

• "Red Wing," Bart Forbes, watercolor, Navajo Chief

• "Ot Way," Bart Forbes, watercolor, Navajo woman

• "Wat-Clurn-Yush," Bart Forbes, watercolor, Navajo Chief

• "Temy," Bart Forbes, watercolor, Navajo young woman

• "Ocean View," Robert Carter, watercolor

• "Carousel Pig," Patricia Baker, watercolor

• "Multiples," Robert Weil, ink & watercolor (print)

• "Oceanside," Dan Poole, oil (print)

• "Pig," James Wyeth, oil (print)

• "Raccoon with Corn," Charles Harper, acrylic (print)